We might as well begin with the most generous interpretation of Elon Musk’s peculiar behavior. For this, we must go back in time—back before the Reddit-flavored subtweets, before the bizarre earnings-call outbursts, before the supervillain cosplaying.

Go back far enough, to another century, to another millennium, where, in the year 1996, you will find Elon Musk, a man in the newspaper business. Elon Musk, a nobody on the cusp of becoming a somebody.

This nobody was not a newspaperman in any real sense of the word. He was certainly not a reporter speaking truth to power in service of the public good, or a journalist probing the complexities of some systemic social ill, or fighting corruption in the name of government accountability. Rather, he was a man who encountered the journalism industry at a pivotal moment, at the golden dawn of the dot-com age, and saw stretched out before him an opportunity for the seizing. And so he seized it.

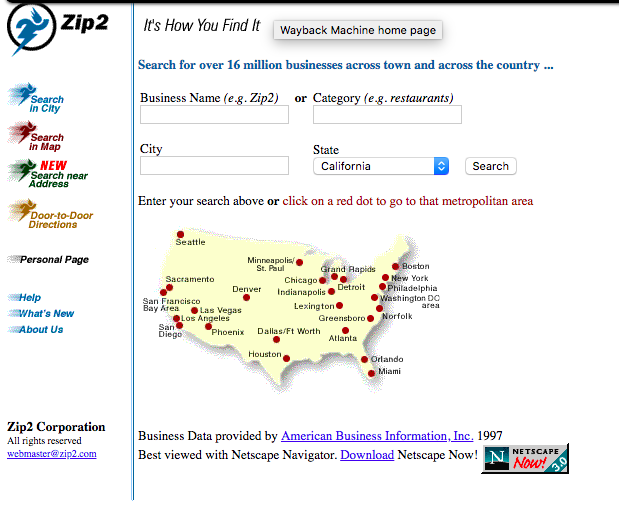

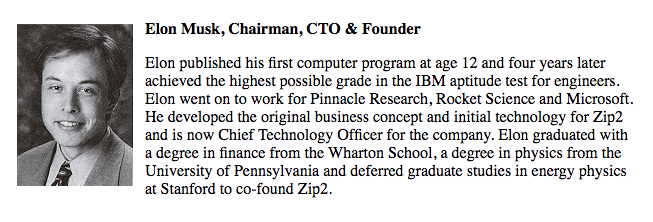

Musk, with his younger brother Kimbal, was one of the founders of the website Zip2, a hybrid business directory and mapping service, which was sold to newspaper publishers as a software package to bring print classifieds, real-estate listings, and auto deals online at the turn of the century. The enterprise seems such a relic now, more than two decades later, that it’s easy to blip over just how revolutionary it once was.

Newspapers were finally but belatedly rattled by the first major technological disruption to the industry since television, and still oblivious about how bad things already were for them. They poured money into the Musk brothers’ venture. Its slogan was, “We Power the Press.”

“Zip2’s technology platform—with its intuitive Java(TM)-based maps, precise door-to-door directions, and internet-to-fax capabilities—is unparalleled,” said Bob Ingle, then a vice president at Knight-Ridder, a major newspaper publisher at the time, in a statement announcing a partnership between the two companies in September 1996. “It helps us deliver dynamic and useful services to our readers, and lets us bring our advertisers into a new medium in a powerful and exciting way."

Knight-Ridder rolled out Zip2 to the websites of its flagship papers, including the Mercury Center (San Jose Mercury News), Philadelphia Online (The Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Daily News), HeraldLink (Miami Herald), Charlotte.com (Charlotte Observer), Pioneer Planet (St. Paul Pioneer Press), and News@Sentinel (Fort Wayne News-Sentinel). Many more publishers followed suit, betting that print media could keep its stranglehold on local advertising in the internet age, as long as the good guys from Silicon Valley were there to provide technical support. “The New York Times has served our readers in New York for over 100 years,” Arthur Sulzberger Jr. said in a statement when the Times announced its partnership with Zip2 in 1997. “This new digital initiative will be a cornerstone of our service for the next 100 years.”

Such partnerships seem hopelessly naïve by today’s standards. Tech platforms have siphoned off most online ad revenue for themselves, and news organizations are largely resigned to operating at the whims of algorithms that are designed to minimize journalism’s reach. (Cough, Facebook, cough.) Editors and publishers should have seen it coming. After all, Musk, for his part, was already “irritated” about his company’s role as a behind-the-scenes force, second to the papers themselves, in the late 1990s. “He believed the company could offer interesting services directly to consumers,” Ashlee Vance wrote in his 2015 biography of Musk, Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future. In other words, why bother with the newspapers at all?

Musk’s frustration, which predated the existence of publishing platforms like Facebook and Twitter, was prescient. His personal fortune was imminent. Sixteen months after the Times announced its partnership with Zip2, Compaq acquired itfor $307 million. Compaq believed Zip2 could enhance AltaVista, which was at the time a strong search-engine competitor to Google. Musk netted $22 million in the deal, and never looked back at the media business. Until now.

It doesn’t matter that the thing that set off Musk was so banal. In an earnings call earlier this month, Musk repeatedly interrupted analysts and insulted them for their questions. “Excuse me,” he said at one point, cutting off a query about capital expenditures. “Boring, bonehead questions are not cool. Next?”

From there, things got very weird, very quickly. In a response to a question about Tesla Model 3 reservations, Musk said, “We’re going to go to YouTube. Sorry. These questions are so dry. They’re killing me!”

Musk then turned over questioning to the YouTuber Galileo Russell, a fanboy investor who has published several fawning videos about Musk and Tesla. For context, one of Russell’s recent videos is titled: “🤑 How Tesla Will Become Profitable in 2018 🤑” and his YouTube bio contains this disclaimer: “Do not assume any facts and numbers in this video are accurate. Always do your own due diligence.”

Once Musk turned to Russell in the earnings call, he let him ask a dozen questions over the course of a long 23 minutes. Russell then recapped the call in a frenetic YouTube video titled, “WE GOT ON THE TESLA EARNINGS CALL.”

“I’m still basically in complete shock right now,” he told his viewers. “Just still shook, processing this entire epic situation.”

Sports reporters have a saying that every good journalist ought to absorb. There’s no cheering in the press box. The idea is this: You can bear witness to the most dramatic, poetic, unbelievable sequence of events ever to transpire in the history of the thing you’re covering, and you better damned well keep your cool anyway. Journalists are not in it to be impressed by the people they interview. They’re in it, on behalf of the public, to get information, to ask tough questions, to give voice to the voiceless. There’s no reason that Russell, the YouTuber, should be held to such a standard if he’s not a professional journalist. But the democratization of publishing technologies means that the lines between professionals and amateurs is ever-blurring, which can be a good thing. But in this case, Musk, a man who made his fortune off of the newspaper industry’s naïveté, is turning to the Russells of the world for public validation in order to sidestep public accountability.

Musk seems to suggest this is warranted because of media bias. “It’s super messed up,” he tweeted on May 14, “that a Tesla crash resulting in a broken ankle is front-page news.” He went on to claim that “the ~40,000 people who died in U.S. auto accidents alone in past year get almost no coverage.” (This is false. Several major outlets published stories about the latest data reflecting overall U.S. traffic deaths. Among them: The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, U.S.A. Today, CNBC,CityLab, The Chicago Tribune, the Associated Press, and more.) Musk is correct that there’s heightened interest in the Tesla’s safety record, but it’s largely because of the way he has hyped the car, repeatedly promising it would win the high-stakes race to put the first truly self-driving car on the market.

Musk kept going. “The holier-than-thou hypocrisy of big media companies who lay claim to the truth, but publish only enough to sugarcoat the lie, is why the public no longer respects them,” he wrote on May 23.

He then announced a plan to start a credibility-ranking site for people to rate journalists and news organizations, and suggested naming it after the Soviet Union’s state-run newspaper: “Going to create a site where the public can rate the core truth of any article & track the credibility score over time of each journalist, editor & publication. Thinking of calling it Pravda.”

In the days that followed, Musk tweeted a link to the Wikipedia page for “critical thinking” and applauded an analysis by a publisher with sketchy alleged ties to a cult. (When called out for praising such a dubious source, Musk seemed unbothered: “Sadly, it had better critical analysis than most non-cult media.”)

Musk’s reference to Pravda, the state-run Communist paper in Soviet-era Russia, was apparently tongue-in-cheek. But Musk’s sarcasm seemed to end there. The idea for a crowdsourced accreditation system—not unlike Mark Zuckerberg’s recent algorithm-human idea for separating out misinformation on his own publishing platform—was, Musk assured skeptics, legitimate. In a rash of tweets that followed, Musk dug in. He ran a simple Twitter poll, asking his audience of nearly 22 million followers whether he should, in fact, create a “media credibility rating site (that also flags propaganda botnets).” He offered two possible responses:

1. Yes, this would be good

2. No, media are awesome

When people overwhelming chose the first option, Musk needled professional journalists—both in direct replies to scrutiny and in a flurry of additional messages broadcast to his 22 million followers. “If you’re in media & don’t want Pravda to exist, write an article telling your readers to vote against it,” he wrote. Then: “Come on media, you can do it! Get more people to vote for you. You are literally the media.” He went on to accuse one journalist of “living in a bubble of self-righteous sanctimony,” adding: “The public doesn’t trust you. This was true *before* the last election & only got worse. Don’t believe me? Run your own poll.”

Musk’s outburst seemed to reach its logical conclusion in his response to the journalist Joshua Topolsky, who implored Musk to stop and think.

Topolsky: Do you think it’s in the interest of powerful people to A: support a free press that exposes their lies, or B: tear it down so their lies are easier to tell? Now ask yourself why the polls would look bad.

Musk: Who do you think *owns* the press? Hello.

Musk rebuffed the suggestion that he was appealing to the anti-Semitic stereotype that Jewish people control the media. The point he was making, he said in a follow-up tweet, was that powerful people own the press. (He did not make the point that many of these owners are, like him, powerful billionaires.)

There is no evidence that Musk actually cares about high-quality journalism. There is no evidence that Musk is motivated by anything other than his own sense of vulnerability, or ego, or his well-documented trollish instincts.

Musk was indignant at comparisons to Donald Trump—another infamous journalist-hater of the moment—but he has clearly invited such comparisons through his behavior. Both men lack restraint in self-publishing. Both appear to be thin-skinned beyond reason. And both use Twitter as a way of bypassing—and engaging with—what they see as an unruly press corps.

The veteran television journalist Lesley Stahl recently shared an anecdote about how Trump responded when she asked him, in 2016, why he bashed journalists so. “I do it to discredit you all and demean you all so when you write negative stories about me no one will believe you,” Stahl says Trump told her.

“Journos hound me constantly for interviews, but I do almost none these days,” Musk tweeted last week. “♥ Twitter as it allows me to bypass journo bs.”

Musk loves a spectacle, which is a useful quality in a person with his résumé. He has complained about journalists in the past—including fixating on seemingly inconsequential inaccuracies. “Bloomberg article today also has oddly false details,” he tweeted in 2014. “I don't eat breakfast at Tesla and drink coffee, not juice.”

He has been compared to Howard Hughes and Ernst Stavro Blofeld, the Bond villain parodied as Dr. Evil in the 1990s Austin Powers films. Musk’s showmanship is well documented. So, too, is the delight he takes in provoking people. “Musk has burned through public-relations staffers with comical efficiency,” Vance wrote. “He tends to take on a lot of the communications work himself, writing news releases and contacting the press as he sees fit.”

Musk often tells of an epiphany he had in the early days of SpaceX, when he realized that people had not given up on truly ambitious space travel. “If you can show people that there is a way, then there is plenty of will.” It is hard to imagine a better line—where there’s a way, there’s a will—to encapsulate the techno-populism upon which Elon Musk built his success.

Here is a detail that any journalist thinking of accepting Musk at his word alone should remember: At one of Musk’s internships at a start-up in Silicon Valley, he’d overheard a disastrous visit from a Yellow Pages spokesperson who couldn’t articulate what the company was doing to adapt to the internet age. Consider how Kimbal, Elon’s brother, described the way they came to Zip2, from Vance’s biography: “Elon said, ‘These guys don’t know what they’re talking about. Maybe this is something we can do.’”

In other words, Musk wasn’t called to the media industry because he was passionate or even particularly interested in journalism, or the role of an independent press in a functioning democracy. (“The arguments journos are using against the public are word for word the same arguments despots use against democracy,” he tweeted on Saturday, apparently without irony.) Musk is typically far more interested in tearing down institutions and reinventing them, than fixing them outright. He can see that the journalism industry has been slow to adapt technologically and culturally to the technologies and rising populism of the political moment. He’s right that the public’s faith in journalism is faltering. And given that Musk has shown so much imagination in remaking entire industries, why shouldn’t he take a big swing at fixing the media?

Musk’s Twitter mentions are full of people celebrating the wisdom of the crowd, and offering to moderate his new site. All this has a very 1990s feel about it, which is, I guess, appropriate. Elon Musk comes from an age where the promise of the open web was utopian and also deeply capitalistic. It was an invitation to do whatever you wanted online, and maybe get outrageously wealthy if you found the right levers to pull. Musk was there, and he cashed in on the promise to help newspapers nail the landing in a leap from print to pixels. (They didn’t.)

Defending himself among naysayers in recent days, Musk made a prediction and a request: “This is going to help journalism, not harm it,” he said. “Please be so kind as to hold your fire until you actually see it.”

“Something needs to be done to reward consistent, high-quality journalism,” he said. “Some in media are absurdly indignant before even seeing the product. Odd.”

Odd, indeed, that to Elon Musk, the product is not the journalism itself. Odd that it would be too simple to reward great journalism by investing in it, or by encouraging his 22 million Twitter followers to support high-quality news organizations through subscriptions. At a time when there’s abundant evidence that the disappearance of local newspapers has denigrated civic life, Musk seems to think that what journalism really needs is another aggregator. But no number of upvotes will save the world.